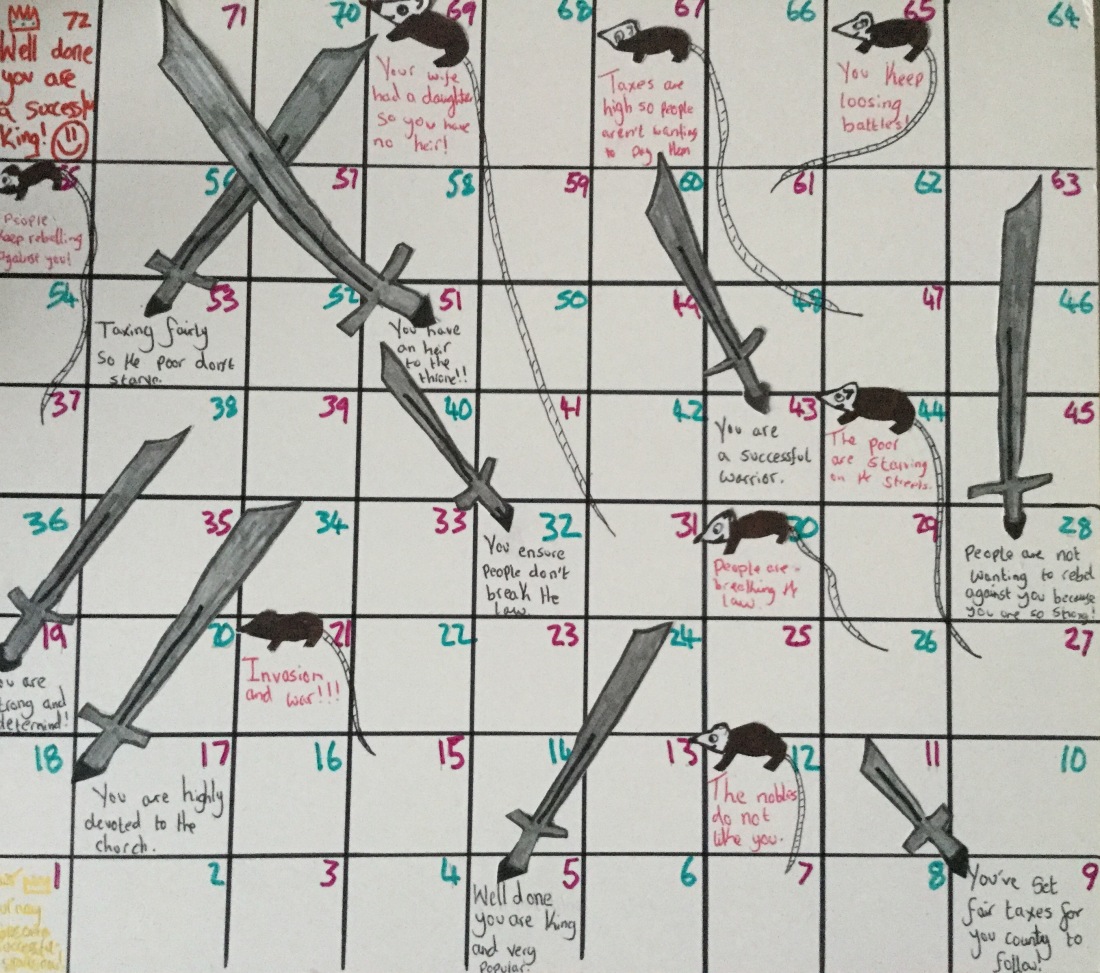

This is a picture of a History homework done by a Y7 of my acquaintance (not at my school, I hasten to add). She had an entire half term to do it. It’s a snakes and ladders style board game about being a successful medieval king.

Beautiful, isn’t it? It took hours. Finding and shaping the board, measuring and drawing the lines, drawing and cutting out the swords and the rats, making the counters, writing the rules. And – oh yes – about 30 minutes deciding what information to write in the squares.

This, then, is the epitome of a Pointless Homework. Ostensibly it’s a History task, but the amount of history that has been learned or used is minimal. It’s good to uphold the law, it’s bad to raise taxes too high, it’s good to have an heir, it’s bad to be invaded. Incisive! The rest of the time has been spent making a game, which hasn’t furthered her knowledge or understanding of history, or honed her historical skills, in the slightest.

(As an aside, this is far from the most egregious example of a pointless homework I’ve come across. That accolade goes to a worksheet I found at my previous school when I began teaching in 1997. It was on medieval punishments. The homework task was this: “Make your own stocks or pillory. Use cardboard or even wood!” Imagine my delight when, returning to the school after a thirteen year absence, I found the self-same worksheet still sitting in the filing cabinet. Like seeing an old, if slightly eccentric, friend.)

Nevertheless, the board game is still pointless and, sadly, far from unique. We’ve all heard of – may even have been party to – homeworks such as “make a model of a cell” (you can insert your own subject’s version here). The occasional twitter threads about this bear witness to the prevalence of such tasks across the curriculum.

Why does this happen? Here are some of the justifications I’ve heard for “Build a model of a castle” and the like, with my comments underneath.

- We’ve done it for a long time.

Longevity does not of itself automatically confer benefits.

2. The children really like it.

a) My child didn’t. If only by the law of averages she cannot have been the only one.

b) Even if they do all like it, that’s no justification. Most children also really like sweets…

3. It’s important that every child gets to do something they are good at, and practical tasks help the ones less good at reading and writing to shine.

Yes, children should be allowed to succeed. But:

a) Children who are not good at reading and writing really need to get better at it, and that will not happen by making board games in a subject that requires good literacy.

b) I would be very surprised to find my daughter spending a whole term of, say, DTE homework researching and writing an essay because “it’s good for children who aren’t good at the practical elements of DTE to be able to shine in this subject.” (NB this is not meant to be a dig at DTE, I’m just inventing an example to make a point.)

4. It helps them with their time management.

At KS3 at least, expecting them sensibly to spread a single task over half a term learn how to spread a task over several weeks is, how shall I put it, ambitious.

What, then, makes a Pointful Homework? To my mind, in my subjects (History and Politics; but more widely too I reckon) it boils down to this: a task which either cements, acquires or applies knowledge. For example:

- Cementing. This is basically learning. Sometimes some time (or all the time, at Michaela and probably elsewhere too) does need to be given over to just getting stuff into brains.

- Acquiring. This could happen in lots of ways. At my school we are big on what we call pre-paration and others might term flipped learning: that is, reading, writing or researching something as the basis for the following lesson. This isn’t a blog about how best to acquire knowledge, but just briefly, don’t say “make notes” unless you’ve taught them exactly what you mean, and and unless you’re sure they can’t just do it on autopilot.

- Applying. It’s not enough to acquire and cement: what’s the point of massive knowledge if you don’t develop the skills to use it effectively? Homework is a good time to practise applying what has been learned, to familiar questions where more cement needs to be applied, or to new ones where the aim is to challenge.

These three types of homework – cementing, acquiring and applying – allow a huge range of interesting, accessible, challenging and, well, pointful activities. From self-quizzing to reading via mind-mapping and MyMaths there are endless possibilities. They also provide a neat sanity check: if your task is doing none of the three things, it could be a Pointless Homework. However, to work well the three types require adherence to the spirit rather than the letter of their law. For example, some knowledge was applied to the making of the board game. Not much though, and only to the extent of “What are the biggest generalisations I can think of that will look good in a game?” Similarly, copying a chunk of text from a book is, strictly speaking, acquiring knowledge. It won’t sink in though.

In the end, what you set for homework will depend hugely on your pedagogical preferences. But if those preferences involve the equivalent of sewing and stuffing a model of a cell, I urge you to reconsider. Cement, acquire, apply. That said, imagine if a child actually did bring a home-made pillory into school.

BREAKING NEWS. The class handed in their board games today. Everyone played their partner’s game with them. Then they took them home, apart from some retained for wall decoration.

LikeLike