Background

If you’ve read Part 1 or Part 2, you can skip this bit and go straight to Part 3. If not, it’ll help.

Car dealers. Marketing executives. Phone companies. Waiters. Teachers. What do we all have in common? We all want people to do what we want. Buy stuff, read stuff, eat stuff, do stuff, don’t do stuff, do stuff differently.

It’s not always easy, though. Usually the stuff you (we) want people to do is stuff they aren’t already doing. Or if they are doing it, they aren’t doing it enough, or in quite the right way. We all know that though. So, why this blog?

Well, there I was, idly flicking through Freakonomics Radio, when I came across an episode called How To Get Anyone To Do Anything. Always a sucker for a quick fix (Get rock hard abs fast without exercise or diet? Yes please!) I dived in.

The episode was an interview with Robert Cialdini, author of Influence: the psychology of persuasion. First published in 1984 and, I’m told, a classic of the genre, it was updated in 2021, hence the podcast. In it, Cialdini takes host Stephen Dubner through some of the key principles that people he calls “compliance professionals” use to get us to do those things they want us to, but which we probably wouldn’t without some gentle encouragement.

It was good. So I bought the book. And in this short series of blogs, I’m going to outline some of Cialdini’s theories and how they might be applicable to various roles in school. He identifies seven “levers of influence” but I’ll stick to four: liking, social proof, authority, and commitment and consistency.

A couple of disclaimers: I haven’t interrogated Cialdini’s sources, nor sought corroboration for his claims. I also note from various reviews that lots of other people have said and written similar things, and no doubt some have contradicted them. Be that as it may, I found lots of the book was relatable and applicable to teaching, and I thought you might too. Here goes.

Part 3: Authority

In this chapter, Cialdini explains that “we are trained from birth to believe that obedience to proper authority is right and disobedience is wrong. This message fills the parental lessons, schoolhouse rhymes, stories and songs of our childhood and is carried forward in the legal, military and political systems we encounter as adults.” We can all relate to this: accepting the advice of a doctor, even if it’s unexpected; obeying police instructions to move along, even if we don’t want to; going to lessons when the bell rings, even if we don’t fancy it. (You can decide for yourself whether the last of those relates to teachers or pupils.)

I know there are exceptions to all of these. Dr Internet can help us challenge our GPs; some people simply haven’t been through Cialdini’s “parental lessons” or stories and songs. But, for the most part, deference to authority exists. So we might as well use it to our advantage.

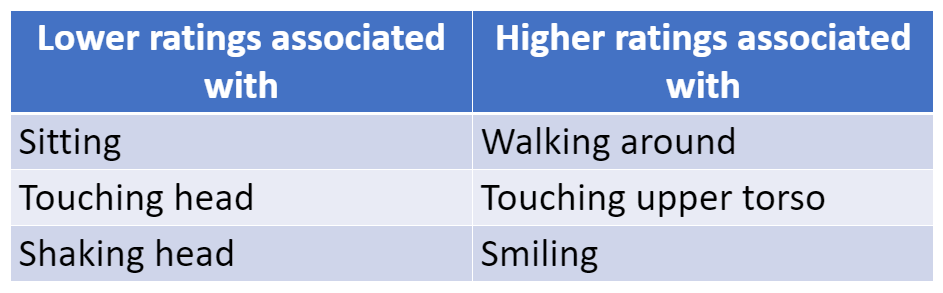

First, let’s make sure people will view us as being in authority. Cialdini notes several ways to do this. One, get a title. Easy: we all have one as teachers, be it Mr, Ms, Dr or whatever. I know some schools are all for first names, but they are the exception. Two, clothing. Again, easy. Wear something smartish and you’re on the way. It’s not as good as a uniform but it helps. Three, trappings: costly clothing, expensive jewellery, a nice car. Much less easy, but according to Cialdini mall shoppers were 79% more likely to fill in a survey and homeowners donated to charity 400% more frequently if the person asking them wore a designer sweater.

Second, be a credible authority. Again, we have a huge head start. People are much more likely to go along with the advice of those they deem to have expertise, and we’re all experts in our subjects – or at least, more expert than the pupils. You’ll have seen this in class, when you’ve given what you know to be a pretty flaky answer to a good question and the student has accepted it, largely because it came from you. (Come on, I’m not the only one.)

Finally, be a trustworthy authority. Often trust takes time to build, for obvious reasons. But a clever way to shortcut this, Cialdini says, to admit to a weakness up front, especially if it will anyway become apparent later. I can imagine doing this: “Now, I always find this section particularly difficult, because there are so many competing opinions/variables/ways for things to wrong.” Come to think of it, that also has the benefit of giving your students permission to fail: if you find it hard, it’s fine for them to find it hard too, so there’s no shame in getting things wrong. Win win.

If I’m honest, this isn’t my favourite of Cialdini’s chapters. There’s so much more to being an effective authority than looking right, sounding right and having a title. The good thing, though, is that we don’t have to do much to ensure we benefit from his ideas, and we can easily add the authority principles to those of liking (part 1 of this super soaraway series of blogs) and social proof (part 2), we really might find that people will do what we ask more often and with less effort on our part.

Summary: keep your title; look the part; revel in your expertise; but remember that there’s lots more to authority than a Rolex.

Next time: commitment and consistency.

It derives from some

It derives from some